MYSTERIES OF MATTER AND ANTIMATTER

Matter, Antimatter... Do you see? These two words sound like something out of a science fiction novel, don't they? That's not so indeed, these two words are a very real and solid part, even the foundation of contemporary physics, and there is more to this subject, of course. In terms of its predicted structure, it also opens the door to some of the possibilities we encounter in those sci-fi novels. For example, if 1 gram of antimatter comes into contact with ordinary matter, it would cause an explosion as effective as a nuclear bomb.

On the other hand, antimatter is thought to be a very efficient source of energy, making it an ideal candidate for future spacecraft propulsion systems. However, there is nothing very surprising about the nature of antimatter. Antimatter is a natural consequence of our ideas about subatomic particles. The British theoretical physicist and mathematician Paul Dirac developed an equation to understand how particles like electrons behave when they approach the speed of light. I won't go into the equation here, but it took Dirac three years to announce this equation after he encountered a two-answer question during his work on the equation. Why? Because his formula gave the first answer as a negatively charged electron, while the second answer was something that didn't exist. It was the kind of answer that nobody said could happen. Dirac was talking about an anti-electron that nobody knew about, almost identical to the electron, with the same mass, the same spin, but a different electric charge. A positively charged electron, hence the name positron. But Dirac's claims did not stop there. What was true for the electron was true for all subatomic particles. If there were quarks, there were also anti-quarks. Anti-quarks formed protons, which in turn gave birth to anti-protons. This sequence actually extended to the atom and then to matter. This is why antimatter had to exist.

In 1932, four years after Dirac's discovery, Carl David Anderson took a photograph and was able to visualize negatively charged electrons, as known as positrons. The Italian physicist Guiseppe Occhialini, a member of the group led by Patrick Blackett at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, confirmed the existence of the positron with their work, and so there was no room for doubt.

Let us now examine the structure of atoms. Most of the mass of atoms is contained in the nucleus, which is made up of protons and neutrons. The particles orbiting the nucleus, called electrons, have much less mass. Electrons are important to us because of their role in electronics: Each electron carries a negative electric charge. (This charge is balanced by the positive charge in a proton.) There are other types of particles, but they are usually only seen in high-energy physics experiments. All the particles that make up normal matter fall into two categories: “baryons” (e.g. protons and neutrons) and ‘leptons’ (e.g. electrons).

You may be starting to get confused, but rest assured, things would be even more confusing if it weren't for the basic principles of nature that we call “conservation laws”. Without the order provided by these laws, there would be complete chaos. When particles interact with each other (e.g. in high-energy accelerators at CERN), certain quantities are always conserved. Energy and electric charge are among these quantities. The “baryon number” and the “lepton number” are also conserved. This is where the concept of antimatter comes into play.

A proton has a baryon number of +1 and a charge of +1. According to the theory, this particle also has an “antiparticle”. The energy of this antiparticle, called an antiproton, is the same, but its baryon number is -1 and its charge is -1. According to the same logic, the electron also has an antiparticle: This antiparticle, called positron, has a positive electric face and a lepton number of -1.

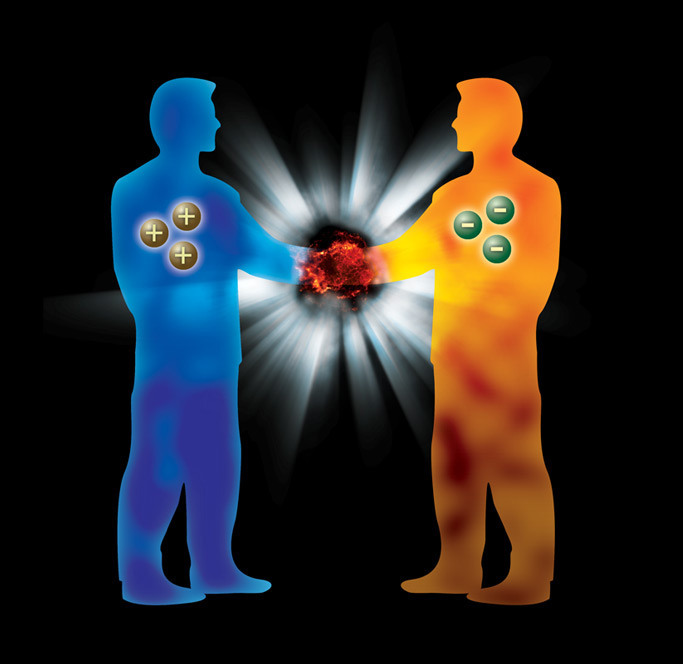

So what happens when an antiproton meets a proton? You probably already know the answer because it is the best known fact about antimatter. Positive and negative baryon numbers cancel each other out. In the same way, positive and negative electric charges and other conserved quantities cancel each other out, leaving only the energy of these two particles. We said energy is one of the conserved quantities, but it is not opposite for both particles, it is the same value. They are annihilated in a burst of energy called a gamma ray. A gamma ray is an electromagnetic wave similar to light, but it carries much more energy than light. The energy it carries is the energy that was just inside the proton and antiproton. “This process, called annihilation, is the only process we know of that can convert mass into energy with 100% efficiency.

The reverse process is also possible. Given enough energy, a particle-antiparticle pair can form. In the case of massive particles like protons and antiprotons, such a pair can only be formed inside high-energy accelerators or in exotic astrophysical processes. But electron-positron pairs are more common: It happens in some types of natural radioactive decay on Earth. We don't exaggerate when we say “common” because, as we'll explain in a moment, even bananas produce positrons. But the antimatter produced in this way can only exist for a very, very short time. Almost as soon as it is formed, it meets its opposite, normal matter, and is destroyed by a small gamma radiation.

Even atoms of normal matter can sometimes produce antiparticles. Radioisotopes are responsible for this. What are these radioisotopes? They are unstable atoms with too few or too many neutrons. There are some common substances that contain small amounts of these isotopes, which decay into more stable forms by emitting high-energy particles. These are usually normal substances (e.g. electrons in the case of beta decay), but some radioisotopes also undergo “beta plus” decay and produce positrons instead of electrons.

Positrons exist for a fraction of a second, then encounter electrons and annihilate, forming gamma rays. But since the energy of a single particle is so small by our everyday standards, these events have no significant impact. We don't feel it. That's a good thing, because there are positron-emitting isotopes in our bodies. The most common is potassium-40, which accounts for one in every 10,000 potassium atoms in nature. This isotope usually decays into regular beta particles, but there is about a 0.001% chance that a positron will be produced.

In this article, we tried to touch upon the mysteries of matter and antimatter. I hope it was enlightening. See you in future publications...

Levent Aslan

13 March 2025

Add Comment